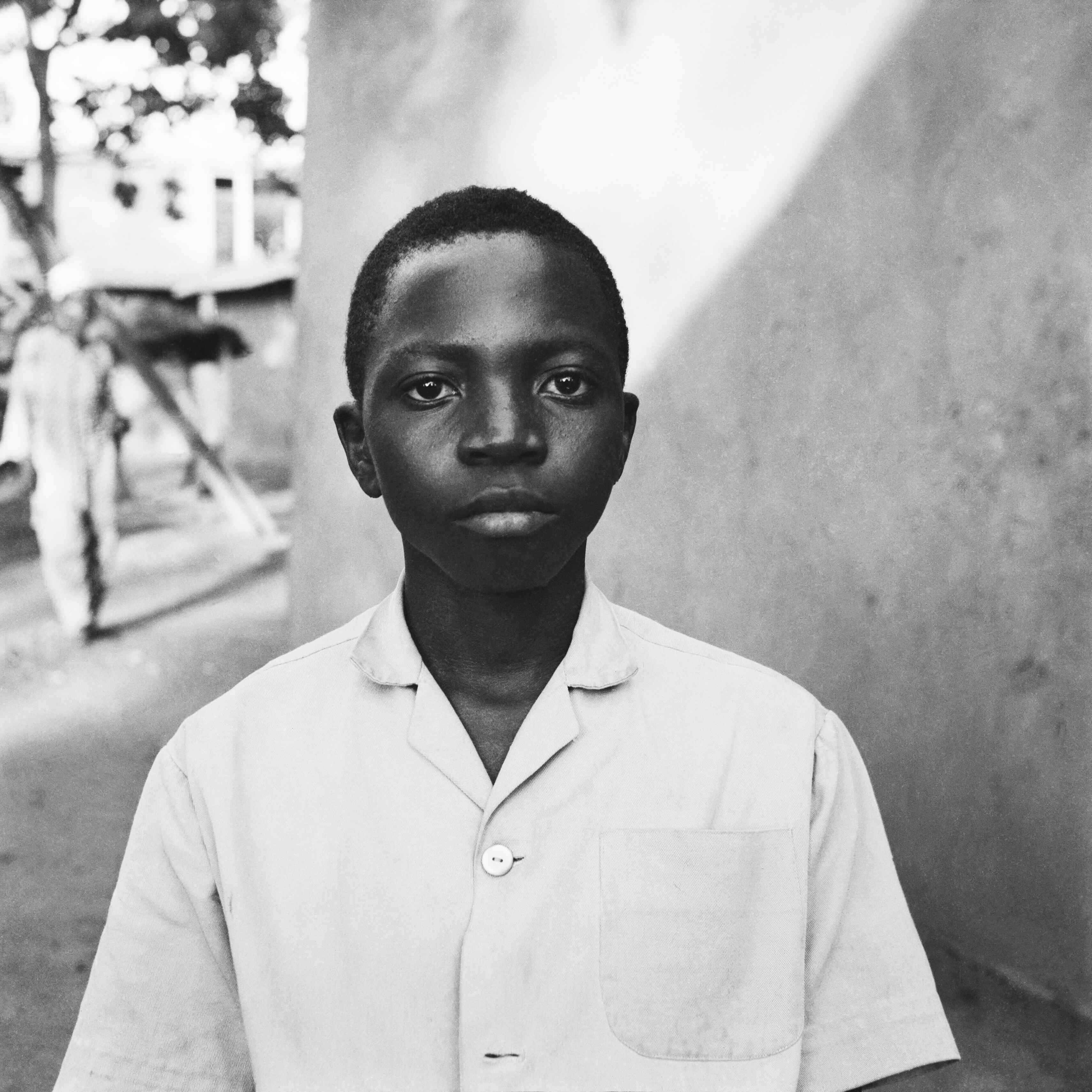

Rachidi Bissiriou Untitled, 1968.

Tête à Têtes: West African Portraiture From Independence Into The 21st Century, a show celebrating West African portraiture, opens this weekend at David Hill Gallery in Notting Hill. Curator and Art Consultant Carrie Scott walks us through the exhibition, detailing the timely relevance of the show and its poignant spot within the history of art as a whole.

Keven Amfo: How did this show come together, and was it challenging to organise everything during the pandemic?

Carrie Scott: This is the second show David Hill and I have done together. We opened our first — an exhibition of Harold Feinstein's work — just before lockdown started, so we don't really know what it is like to collaborate without restrictions in place. Gratefully, we have found a wonderful and natural rhythm in working together from afar. Planning Tête à Têtes was no exception. It happened organically.

Prompted and propelled by the brutal killing of George Floyd, David and I realised how close we were aligned on the inalienable fact that Black Lives Matter, and we wanted to do something to help affect change and support anti-racism. Over the late spring and early summer, we launched two successful print campaigns with Aria Isadora and Larry Fink to raise money for Until Freedom, a social justice organisation working to address systemic and racial injustice. David and I then naturally started talking about underrepresentation in art, and that's when David said something along the lines of 'maybe we should collaborate on the show I have lined up for the fall. It's centred on West African Photographers, and will debut works by one photographer whose work has never been exhibited.' He showed me a small handful of compositions, and I was utterly blown away. They were fresh, undeniably cool and entirely optimistic. It felt like work I needed to see at this moment; work I needed to support; work the world should know about.

Leonce Raphael Agbodjélou Untitled #2 (Egungun series), 2011

KA: What is important about each of the artists being shown?

CS: This moment or movement, if we can call it that, began in Ghana in 1957 as independence from colonial rule swept across Africa. This newfound freedom saw people embracing fashion and music in a whole new way. Photography boomed, creativity blossomed. And portraits, in particular, were used to establish socioeconomic status and mark prestige within the community. The photographs in our exhibition capture a whole host of characters in their finery — desiring to be seen in a new light — with each photographer forging a unique aesthetic.

The work of Mali's Malick Sidibé shows a vibrant youth culture at dance clubs, parties and sporting events; people enjoying their freedom and intoxicated with the new Western styles in music and fashion. 'For me, photography is all about youth,' he said. We see relaxed groups of men and women being themselves. In 2007, Sidibé was awarded the Venice Biennale's Golden Lion Award for Lifetime Achievement, the first time this had been given to either a photographer or someone of African descent.

Sanlé Sory also caught the exuberance of West African youth immersed in new styles of music and dancing in the first decades of African independence. In his images, you can almost hear a joyful soundtrack of laughter and song playing in the background. Many of Sory's photographs also show the merging of tradition and modernity that was beginning to take shape. Pair that with a pin-sharp focus and these compositions become entirely seductive. It's just amazing to me that Sory's work was first shown at David's gallery only three years ago. A year later, Sory became the first African photographer to be given a solo show at an American museum (Art Institute of Chicago).

The photographs by Beninese photographer Leonce Raphael Agbodjélou are quite different in feel to the other black and white works in the show. Included in the exhibition are two colour portraits of Yoruba men dressed in traditional Egungun costume; they are stand-ins for spiritual ancestors and emerge for masquerades that attract big crowds. Agbodjelou's lens here is focused on ancestry and detail and how these traditions can shape counter-cultural narratives.

Rachidi Bissiriou's work has never before been exhibited. It has not been shown in Kétou, the village where he lives in central Benin, or anywhere else. The only people to have seen these photographs before are the artist, the subjects and their families and friends. Bissiriou spent three decades using his Yashica twin-lens camera to photograph the locals exactly as he found them. Now retired, Bissiriou produced an extraordinary series of the villagers. Though some images are more than 40 years old, the lighting and composition give them a remarkably contemporary and relevant feel.

Malick Sidibé Les J. S. Copains 28.08.65

KA: Do you find their work to be inherently similar, either stylistically or technically?

CS: While the images in the exhibition are certainly linked by the fact that they are portraits of one kind or another, each approach is different. So no, I don't think there is anything that makes this work inherently similar.

Having said that, I do think there's a real celebratory nature to all of the work in this show, and that is potentially tied up in this newfound freedom that came after Africa started to gain independence. In each portrait, the sitter's individual style shines through, which is testament to the artist's charisma and rapport with his subjects but also the artist's love for the sitter's personality which is, again, tied up in this newfound freedom.

KA: Leonce Raphael Agbodjélou's photos appear, at first glance, different than those by the other three photographers in the show. How are they actually similar?

CS: While you cannot see the faces of the people in Agbodjélou's compositions, the stillness in each image makes them as much a portrait as any of the other work in the show. Through Agbodjélou's lens, we focus on the magnificent detail of the Egungun costumes — layers of rich cloth panels, beads, shells, skins and all manner of other things that take up to a year to make. Typically, we wouldn't be able to see this level of detail while watching an Egungun masquerade because they would be moving too much, but here Agbodjélou has frozen these figures for us, giving us a window and a portrait of a culture we should know.

Sanlé Sory Les Afro-Pop, 1973.

KA: How are the works being shown relevant to what's happening in the world today?

CS: I sort of touched on this in the first question, and while I don't want to get on a proverbial soapbox, I think it is important to talk about the larger issue at play. David had been planning to do this exhibition for a year, but with the heightened and much needed new awareness around racism, and what it actually means to be anti-racist, this exhibition feels even more critical than it must have when David first added it to the gallery's exhibition schedule.

As kids, we were taught that history was fixed and somehow explicitly accurate. It's not. History is told, mostly from one perspective — typically the victor's, and art history is no different. The western world has weaved the History of Art together using the artworks created by a few 'good, white men.' But here's the thing — history is not sealed in concrete. We aren't stuck with the Art History we've been told. We can rewrite the past with fresh perspectives. We can excavate new pictures and new stories. We don't need to stick with the mostly white male narratives we have seen and heard for so long. We can revise. We can unearth the history and aesthetics that have been suppressed by omission. And that's precisely what this exhibition is about, featuring artworks that deserve to be part of the broader history of photography; fortunately, we aren't alone in taking this step. Institutions as prestigious as Oxford University's Pitts Rivers Museum are addressing their problematic colonial past and attempting to educate visitors about the way many of the museums' 500,000 artefacts were violently taken as a result of British imperial expansion. They are even removing those objects and others that reinforce racist and stereotypical thinking. There is finally a meaningful shift happening. In my opinion, this has been a long time coming.

Over the past decade, there has been a sense in the art world that equity was on the horizon: emerging female artists landed high-profile solo shows, museums were staging exhibitions themed around People of Colour and minorities, grants were being awarded to long-neglected artists. But the numbers don't lie. Between 2008 and 2018, only 11% of art acquired by the top museums in the US were by women. Pair these numbers with how many works by POC were acquired by museums — approximately 2.3% for the same period — and the truth is plain to see; the art world is decidedly one dimensional. Tête à Têtes is our attempt to show another side of the story. We attempt to show West African societies as they are — rich in their own cultural identity and beauty — rather than war-torn and hungry as these communities are so often portrayed in 'first world' media.

In lieu of a traditional opening, the curatorial journey of Tête à Têtes: West African Portraiture From Independence Into The 21st Century is detailed in a 15-minute film. Providing an insider glimpse and detailed insight into the artists and their works, it can be viewed exclusively by readers for 48 hours via this link before it is released to the public.

For info on Quintessentially's Art Patrons programme, please contact us here.